Note: All the ideas and content here are mine except as noted, and may not be used without permission.

I had another discussion with a journalist last week about standardized tests in the college admissions process. And at the end of it, I decided it will probably be my last.

The reasons are many, and I want to outline them. Mostly, though, I want to make a few points to respond to the shopworn justifications ACT and College Board (aka “The Agencies”) trot out over and over and over again, ad nauseam, to justify the continued existence of their tests.

Finally, I want to make a proposal to end the battle once and for all.

-0-

I’m just frankly tired of explaining the same stuff all the time. It wouldn’t be so bad, but so many people come at this discussion with so many assumptions about what tests are and are not; and the time spent attempting to disabuse them of those long-entrenched biases is work in and of itself. It’s especially hard when that person probably benefited from being a good tester all their life.

Mostly, though, I’m tired of hearing myself talk about it. After all, there are only so many ways to say this stuff. I’m reminded of East Coker, and since we’ll be talking about anti-Semites later, it seems fitting to invoke T.S. Eliot:

So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years—

Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l’entre deux guerres

Trying to use words, and every attempt

Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate—but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

I have seen documentaries of musicians who talk about the signature song that the audience expects them to sing every night they perform, and how they both love it and hate it. If Mick Jagger has Satisfaction, and Elton John has Your Song, then The Trouble with the SAT and ACT is my burden. Let someone else sing it for a while; Elvis and Frank did My Way differently, and we’re better for both versions. This is as much for the good of the crusade, and for the good of the profession, as it is for me.

-o-

Now, let’s talk about what happens every time The Agencies, under some pressure, want to appeal to the masses and convince them of the value of standardized tests in admissions. You’ll see a lot of content about this in the near future as California debates eliminating tests for admission to the UC System. As the old adage goes, when California gets a cold, America sneezes. And when California gets a cold, The Agencies get pneumonia.

So get ready: There seem to be about eight or ten tried and true aphorisms, depending on how you count, and I want to share them here, along with my response to them.

I’m not going to tell you what to think. I’m going to tell you what I think, and you can feel free to agree or disagree, of course. It’s yours to do with as you wish.

In no particular order:

Point 1: The tests are standardized and thus fair because everyone takes the same exam. This is known as the “Common Yardstick” theory, and is partially correct, in the sense that the ACT and SAT are normed tests, which means a) half the people will score in the top half, and half the people will score in the bottom half, and b) your position in one administration of the test is likely to be close to your position in another. That’s what these tests do: They sort people on some particular skill or ability. What this skill or ability is, and how much it contributes to your potential to succeed in college, is still undefined: Not even psychometricians seem to know for sure (more on this further down the post).

So, no, Gus from Topeka, despite your confidence on the Internet, you don’t know either.

But this “standardization” does not mean everyone has the same chance to do well on those tests; it’s not like the competition is fair. We don’t have a national curriculum that the test can measure a student’s achievement against, for starters. We don’t even have a standard approach to teaching mathematics.

Even if we did, taking multiple-choice tests is a skill unto itself, and not every student has access to test prep to figure out the test strategy; not every student can pay to take the test multiple times (a few fee waivers notwithstanding); not every student knows to take the test five times and learn from their mistakes before they ever sit for it officially (because improving too much on official tests attracts the attention of The Agencies). Not every student has a test-obsessed school district that includes test-prep (often, tragically, at the expense of instructional time); not everyone goes to schools where (tragically) subject tests in classes like English are designed as multiple choice to ensure students learn how to work and think that way.

People often wonder how test prep can give you an advantage: Imagine you have a brand new video game, and you have to pick a winner of a single match: Player A is a video game expert, but has never played this particular game; Player B is a pretty good gamer who’s played the game ten times. Which one do you pick? Maybe–just maybe–you said Player A (although I’d disagree.) What if Player B spent six hours with the video game designer prior to playing it? Or had someone who’s played it 100 times coach her before those ten trials?

There is overhead in the test, and wealth gives you the advantage in taking it. If you don’t believe it, watch The Test and the Art of Thinking, which you can rent online for a few bucks. You’ll see how a high-priced tutor can teach you to get the right answer without ever reading the question, in what was the best scene in the film for me.

OK, I lied. The best scene was Akil Bello asking if England has a 4th of July.

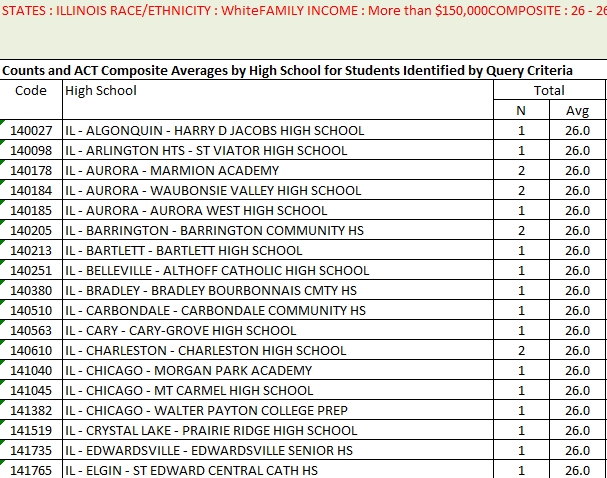

The effects of wealth and ethnicity (which are tightly tied together in America) are shown in ACT data, which they make available in their product EIS. (People–including people at ACT–have asked how I get this data: You can extract it in fairly precise detail, using the export function. You get a sheet that looks like this. In this case, it shows how many White students with self-reported family income of $150,000 + scored exactly a 26 Composite, and it’s broken down by high school. This example was from 2011, I believe):

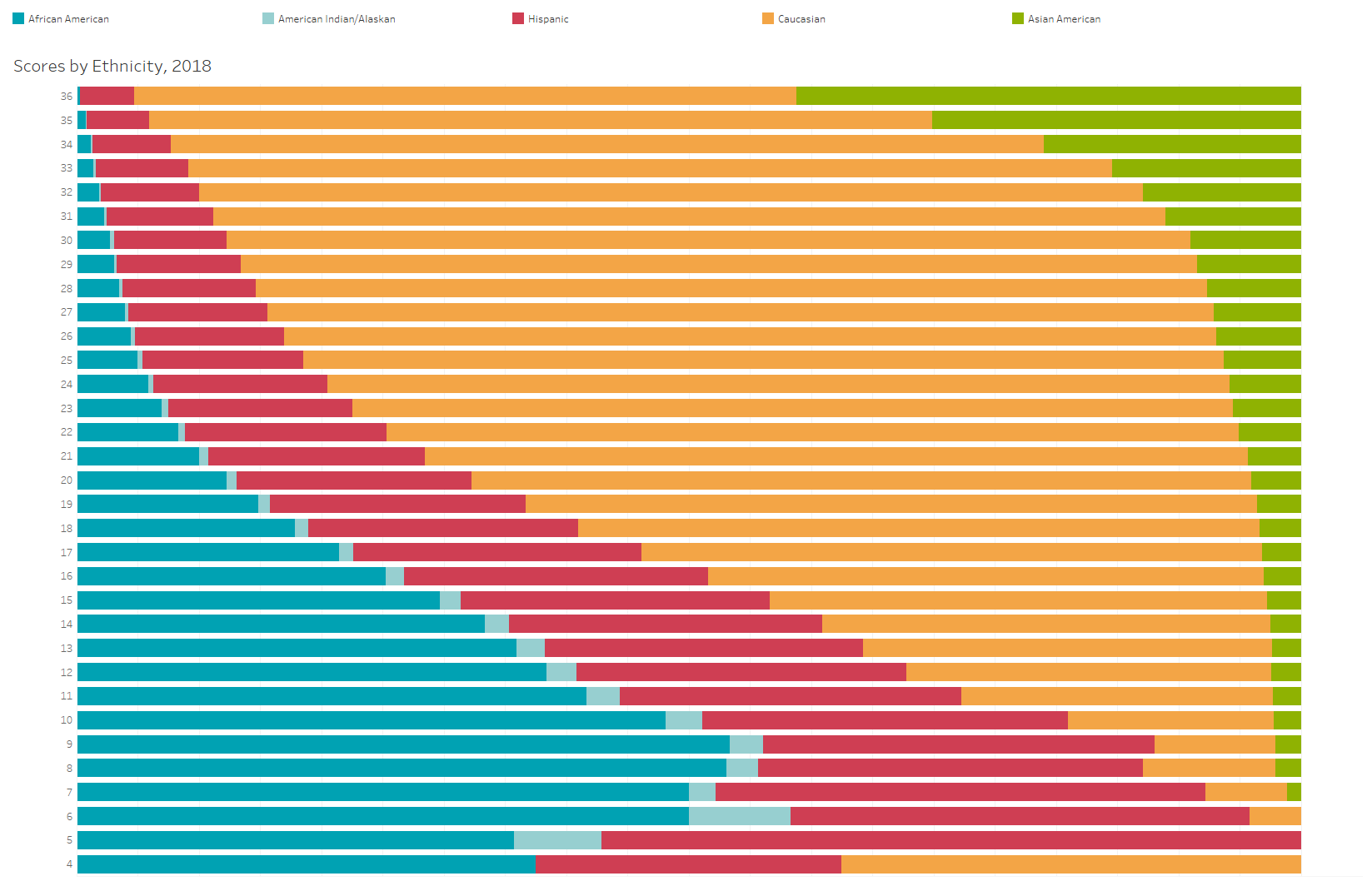

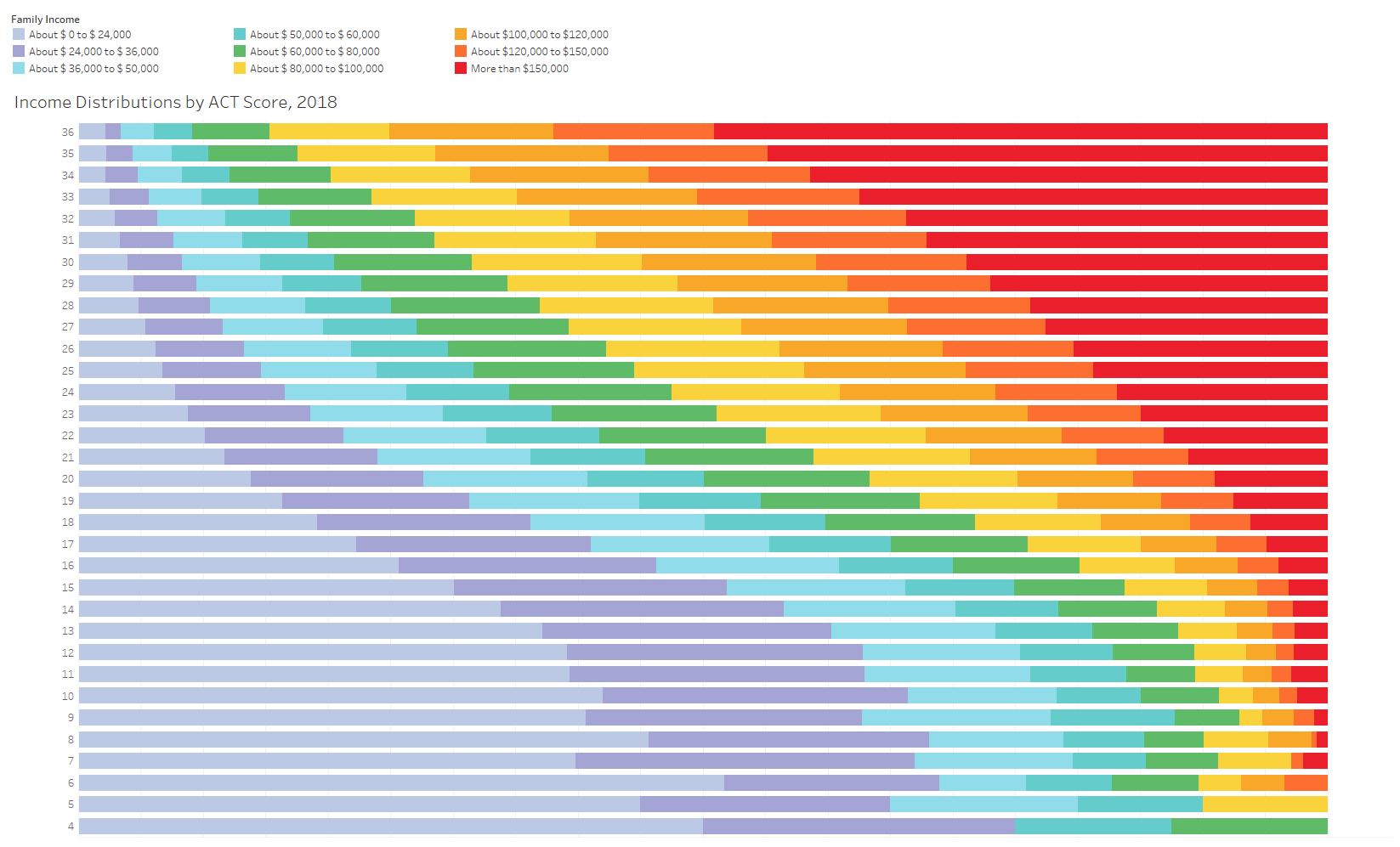

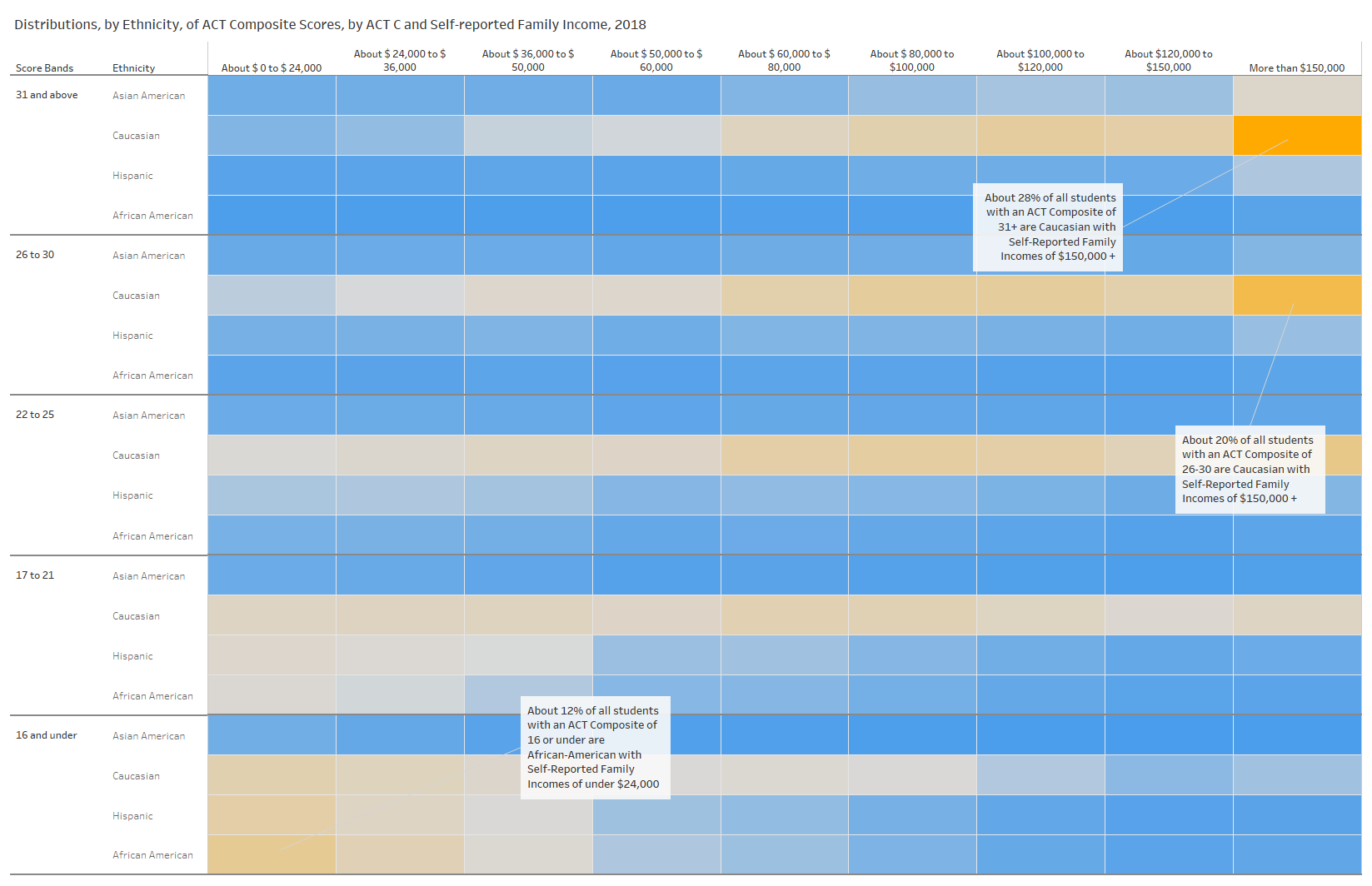

Do this enough times, with all the combinations of ethnicity, income, and composite score, and you can create a nice little database. Load that data into Tableau and start playing with it, and you get some interesting pictures of test performance. (These are all screenshots from my time at DePaul. My current employer is not a subscriber to EIS).

Note: These numbers may not be surgically precise, but I think they’re pretty accurate, and certainly close enough to draw conclusions. If ACT wants to provide actual data, I’ll be happy to post that.

Like this. It shows ACT Composite score, and the breakdown of each composite score. High scores are at the top. For instance, of all the students who scored a 33, about 15% were Asian (green), and 75% were Caucasian (gold). Do you notice a trend? And do you see what happens to the pool when you think a 30 is the floor for your student body?

On all of these charts, right click and open in a new window to see them larger.

This is the same concept, except colored by income. High scores are at the top; high income is red, and the progression of incomes should not be hard to figure out. Do you notice a trend?

What strikes me on those two charts is the absolutely perfect step-wise progressions of the relationships. It’s almost like the tests are designed with that outcome in mind.

And here’s the result of looking at this by income and ethnicity (which, again, in America track each other closely.) Look at this chart to see who gets a 31+ in America. And who doesn’t. The darker orange colored boxes show higher concentrations among the score bands; darker blue shows lower. Do you notice any trends?

You decide. If these were just scores, and understood as accumulated cultural capital, it might not matter. But these scores make a huge difference in who gets into college in America, and perhaps more to the point, who gets into which college. If that fact doesn’t bother you, you’re effectively saying that you believe low-income students of all races are dumb, and unworthy of a chance at education. As David Brooks wrote, “…let’s say you work at a university or a college. You are a cog in the one of the great inequality producing machines this country has known.”

You OK with that?

I’ve seen a lot of presentations on higher education in my time in the profession. Several stand out in my mind: At my first conference, Fred Hargadon, who was a last-minute replacement for a speaker whose name is now lost to history, said, “In all my years in this job, I’ve learned only two things: That the block on which you’re born has more to do with where you end up in life than any other single factor, and if we had to choose the worst age to pick a college, it would be 17.” But the best presentation I ever saw was given by Harry Brighouse, a professor at UW Madison. In speaking about the differences in the American and British education systems, he pointed out that (paraphrasing) “we tend to equate merit and achievement, but no one who is meritorious gets to achieve anything unless someone invests in them.” That simultaneous equivalence of, and distinction between, Merit and Achievement sent a clap of thunder through my consciousness that stays with me until this day. The summary of his presentation has been removed from the conference website, but it’s here in pdf if you want to read it.

Point 2: The “Diamond in the Rough” (DITR) theory. This heart-warming approach posits that there are low-income and/or first-generation, and/or students of color out there who will be disadvantaged if tests go away, because the tests help them get identified as bright. And of course, this is not completely wrong, but it’s only true because a) some college admissions officers don’t know much about tests, and b) they do know that people ask them about average test scores all the time, again (here comes the absurdity) even though they vary so strongly with wealth. If you get the impression of a dog chasing its tail, you wouldn’t be wrong.

Not coincidentally, The DITR aphorism is also designed to appeal to people who don’t think critically.

Some propositional logic might be in order. It was perhaps the best class I ever took in college, but I don’t expect you to dive deeply into it, unless it’s raining and you have nothing better to do. Let me outline the challenge here.

These high-scoring students are bright; the tests measure something, but again whether that something is valuable is another question.

It’s a sad state of affairs in US higher ed that students from less advantaged background need the equivalent of a lottery to get a chance, but that’s exactly how things shake out. And the corollary to this is that there are loads of smart, capable students with lots of maturity and abilities no test can measure at the other end of the standardized testing scale who get overlooked because of the tests. That’s the cost no one ever considers when they spout the “Diamond in the Rough” argument: Human potential that goes unrecognized because of a test, developed by private companies whose only obligation is to themselves. It’s great that one student gets a chance. But what about the 500 who don’t?

Back to logic. When you say, “high-testers are smart” many people jump to an inappropriate conclusion that says, “non-high-testers are not smart.” That’s the problem: All S is P in no way implies that All Non-S are Non-P. (All poodles are dogs, but all non-poodles are not non-dogs, in case you’re having some trouble deciphering this.)

Tests like this have low rates false-positives. But they also have high rates of false negatives. That’s a problem, but it’s also the reason (along with the income correlation) super-selective institutions like them: With few slots to give out, they want some assurance of “it,” whatever “it” is. And the flotsam and jetsam of low-income, first-generation, students of color left behind are just the cost of doing business.

The perception that high SAT averages in your freshman class means your students are “smart,” when it can also mean you’ve built a gate to keep poor people out, is a double whammy of brand goodness for the nation’s “elite” institutions. As I wrote once, “Perhaps ‘elite” really means ‘uncluttered by poor people’.”

At the same conference (maybe not the same year, though) where I heard Harry Brighouse, I heard the Dean of Admissions at an Ivy League institution say–in public, in a presentation–that they spent “all their time” looking for low-income students, which they defined as “family incomes of under $60,000.” (Median family income at the time was about $55,000.) Unfortunately, in the words of this dean, and despite these Herculean efforts, they “just could not find enough low-income students who could do the work at the university.”

Two things struck me about this statement: One was the fact that this university was notorious for not enrolling many low-income students, so how could the dean know that, but more concerning was the ease with which it was uttered, as though it had been floated out in meetings so many times at this university without being challenged that it seemed as natural as the leaves returning to the trees in the spring.

Point 3: Grade inflation makes grades meaningless, and thus we need tests.

Let me re-write that proposition to put things on equal footing. If you believe grade inflation makes grades meaningless, then let’s add more meaningless measures to the equation. That doesn’t sound quite as smart, does it?

Just check out Saul Geieser’s work at UC Berkeley. If that’s not enough to demonstrate that over a long period of time, HS GPA is really all that has ever mattered, here’s a little more to augment our discussion.

An analysis by James Murphy suggesting the data on grade inflation aren’t all that.

And Paul Tough’s book, “The Years that Matter Most” also pointed out that the College Board’s public relations campaign using a paper by Hurwitz and Lee on Grade Inflation (thus implicitly supporting the use of tests) in a book titled Measuring Success had language and conclusions not supported by the data. In fact, the data contradicted it, (Tough says it’s right there in Tables 3.9 and 3.10). The SAT hurt low-income students, rather than helped them in the face of non-existent grade inflation.

By the way, in The Big Test, we learn that UC Berkeley originally adopted the SAT in the early 1960’s because of concerns about “grade inflation.” It’s on page 172. (Others have suggested that Berkeley wanted to be considered in the same conversation with Harvard, and there may be elements of truth to that as well.)

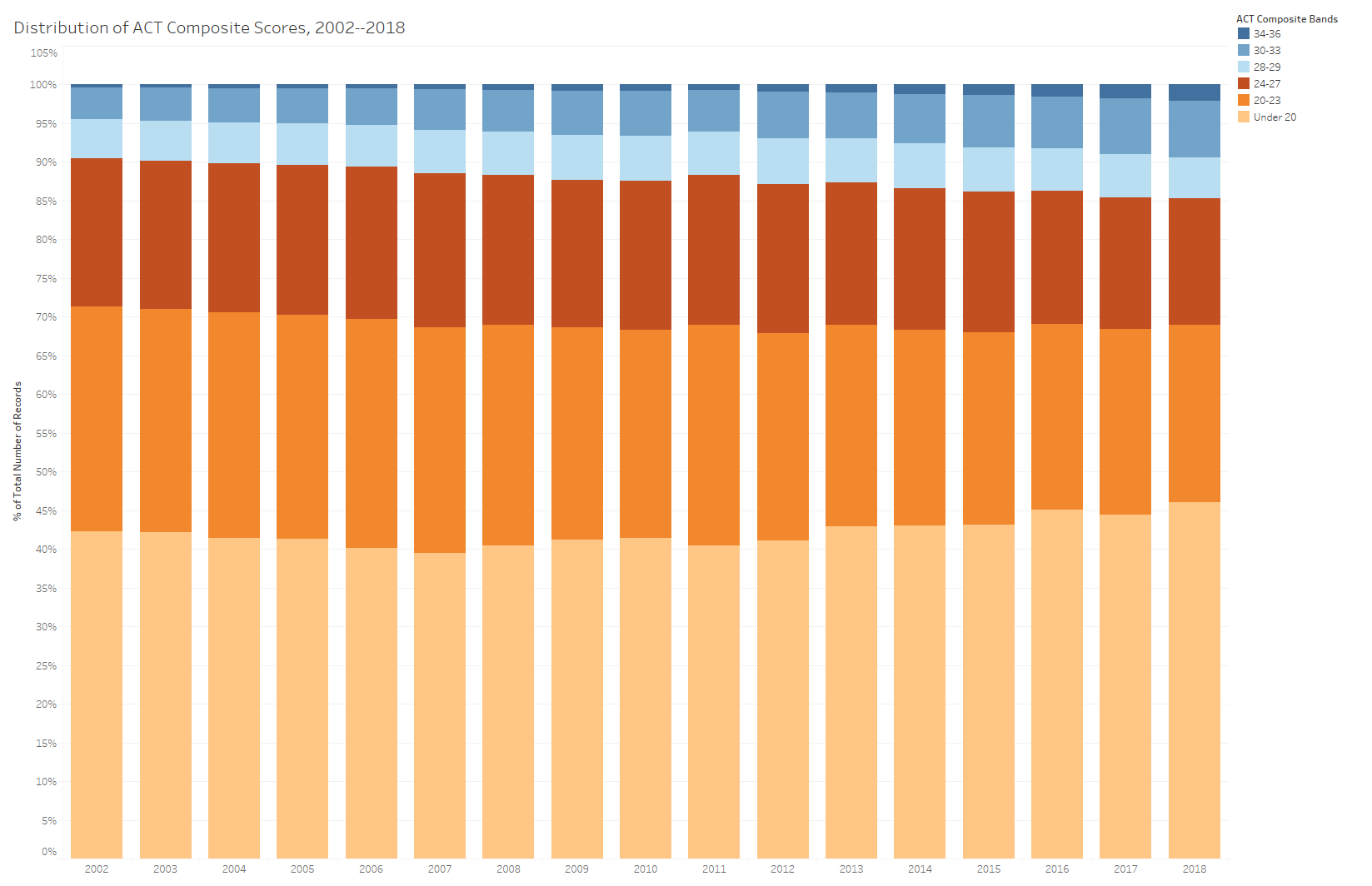

While we’re talking about inflation, take a look at the rise in high scores on the ACT over time (in the next chart down). Let me point out a few tidbits here: A higher percentage of testers (just over 7%) scored 30-33 in 2018 than scored 28-29 in 2002 (about 5%). In 2002, only about one-third of one percent (0.33%) of testers scored 34 and above. By 2018, that was over 2%, an increase of over 500%. Which is worse? Grade inflation on tests in school where, presumably, everyone can master content? Or test inflation on a test that’s supposed to be normed? You decide.

College Board data is not as easy to obtain, and the SAT is on its third iteration since 2005, so long-term trends aren’t available and would be hard to interpret even if they were, but given the nature of business, I wouldn’t be surprised if they were similar.

By the way, The Agencies could release detailed reports like this if they wanted to, but for some reason, they don’t. If I worked at a school district that was measured by these tests, or in a state department of education, I think I’d sure as hell ask them why not. But that’s just me, and this is just the nation’s educational system, so maybe it’s not that important to everyone else.

Point 4: Don’t blame the tests for telling the cold hard truth. The CEO of ACT even wrote a complete blog post about this, in which he used some very bad analogies about doctors and patient health. Correct, we don’t blame doctors or thermometers when a patient has a fever. Obviously.

But what if that thermometer reading got the patient quarantined forever, even though the fever lasted a day? What if the doctor used the wrong type of thermometer? What if the doctor used the test results to conclude the patient had cancer when she only had a virus (or vice versa)? What if, during a job interview, the boss said, “Your resume looks great, but I see you had a fever ten years ago. Tell me about that,” with a suspicious scowl. We’d probably consider all of those things a problem.

Analogies are fun, but no longer on the SAT.

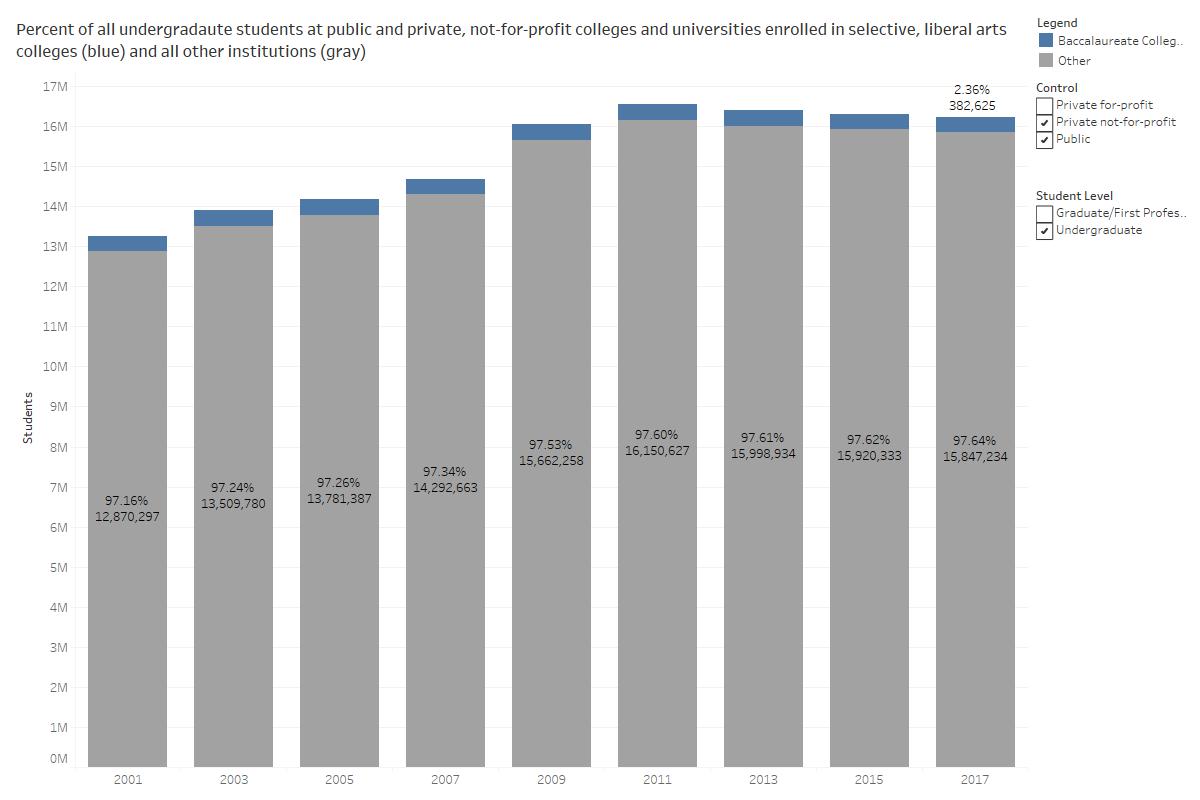

Point 5: Removing the tests doesn’t accomplish the diversity objectives that are often an explicit or implicit goal of going test optional. This is a big claim, because it’s based on “research.” That research looks at 32 small, liberal arts colleges that adopted test-optional admissions practices. There is no suggestion anywhere that these findings can be generalized to the other colleges and universities in America, except, it seems, by the people who want so badly for it to be true.

In case you were wondering, those selective liberal arts colleges enroll about 2.36% of all college students in the US. And it’s hardly a random sample; about 70% of all students attend public institutions.

Here is perhaps a more representative study, using unit record data from a lot of different types of colleges over a long period of time. Test optional doesn’t always work in increasing diversity (no approach ever works all the time, duh), but it works frequently enough to suggest there is something at play.

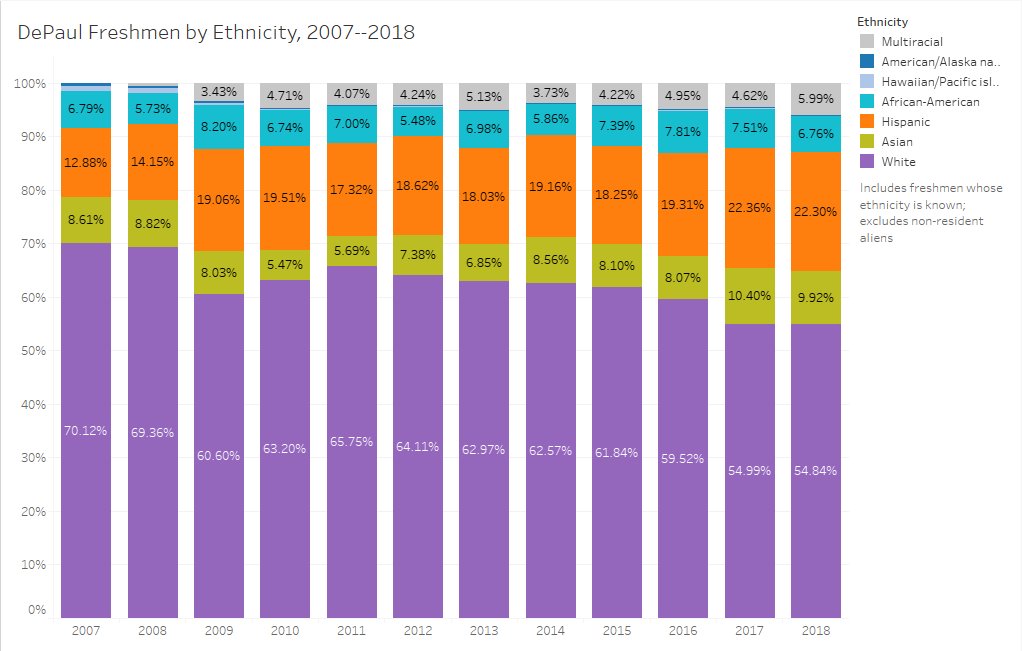

And while it’s anecdotal, here is a snapshot of the freshman class at DePaul, where I worked for 17 years. DePaul announced a test-optional admissions policy in Spring of 2011 for the Fall, 2012 entering class; and in case you’re wondering, that bump in Hispanic students between 2008 and 2009 (before test optional) was driven by a change in federal guidelines about collecting and reporting ethnicity, which went into effect in 2009 and have remained the same since then. Most colleges saw similar bumps in 2009.

For the skeptics who think students admitted via test-optional policies are doomed to fail, here are some of the results from a study commissioned by EM at DePaul and conducted by an external agency, of the performance of test-optional students. They are remarkably similar to other studies I’ve seen, showing little difference in the two groups. Remember, football players at Notre Dame, with SAT means 350 points or more below the rest of the student body, have similar graduation rates. Just ask them if you don’t believe me. Well, the graduation rate part, anyway.

The results at DePaul were good, even though a) there was a difference in six points on mean ACT composite scores between the two groups (19 vs. 26), and b) there were many factors we’d think would contribute to or hinder first year success, like the need to work, commuting vs. living on campus, or parental attainment, that were not included in the analysis.

Graduation rates are even harder to predict, but we saw almost identical (within one point) performance of test-optional students over time compared to test-submitters. My personal preference, however, is to look at first year GPA as the outcome: A successful year–all other things not withstanding–suggests the admission decision, at least, was a good one.

GPA after one year:

|

Descriptive Statistics | |||

| Dependent Variable: Cum_GPA_Y1 | |||

| comparison groups | Mean | Std. Deviation | N |

| (1) Test Optional | 3.1404 | .55619 | 187 |

| (2) Matched Group | 3.2099 | .61763 | 406 |

| (3) Rest of Base Pop | 3.2881 | .57167 | 3842 |

| Total | 3.2747 | .57639 | 4435 |

Retention to Year 2:

|

Descriptive Statistics | |||

| Dependent Variable: RET_Y1.Y2 | |||

| comparison_groups | Mean | Std. Deviation | N |

| (1) Test Optional | .8466 | .36137 | 189 |

| (2) Matched Group | .8252 | .38022 | 412 |

| (3) Rest of Base Pop | .8621 | .34481 | 3866 |

| Total | .8581 | .34902 | 4467 |

Credits earned (DePaul is on a quarter system, and 48 credits is a full load for one year):

|

Estimates | ||||

| Dependent Variable: Cum_Credits_Earned_Y1 | ||||

| comparison_groups | Mean | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| (1) Test Optional | 42.903 | .698 | 41.534 | 44.272 |

| (2) Matched Group | 43.896 | .474 | 42.966 | 44.825 |

| (3) Rest of Base Pop | 44.220 | .154 | 43.918 | 44.522 |

Point 6: More information is better. Well, often it is. And in this case, it may be. Slightly. Most models show a slight gain in predictive power with tests. Predictive models are funny, however, and Brian Zucker at Human Capital once told me he dumped zodiac sign into a model, and it added to the equation about as much as test scores did. This makes some sense, as zodiac sign can indicate how much older or younger you are than your peers in the class, and at age 18, eleven months of development can be meaningful. Most colleges are zodiac optional, however. For now.

Two points: First, predicting human behavior is really hard, and I’ve often described admissions as a crap shoot. The best models, when trying to predict GPA performance of freshmen, show an r-squared value of maybe .35. In other words, only about 35% of the variance in first-year performance can be explained by using the things you collect at the point of admission. Because GPA is better, taking tests out only decreases that a little bit. The rest (65%) is unexplained by anything we collect in the admissions process. Your results may vary, so do your own damn research. As I’ve said before, if tests work well for you, you’d be foolish to eliminate them.

And this is true of students with similar profiles at similar high schools. Why? Think of all the things that might influence grades in the freshman year: Distance from home; boyfriends/girlfriends; match with an appropriate major; the need to work; the need to support a family member; whether this school was your first or fifth choice; whether your freedom led you to party too much and study too little; how much you like your roommate; and even whether you have an X-Box in your room and no parents to nag you to do your assignments.

Second, again, is the cost of the tests vis-à-vis the benefit they add. I had one Chicago Public School teacher tell me that 16% of his instructional class time was spent prepping classes for mandated standardized tests. That’s a real opportunity cost. Thousands of students with false negatives (low scores even though they’re bright and good students) won’t consider a school reporting mean test scores higher than their own because they don’t always understand how distributions work, and they don’t realize the limitations of the test in predicting their academic success.

Point 7: Everything else we use is bad, so we need tests. In other words, this soup is too spicy, so let’s add some salt.

I’ve written about the unfairness of some admissions criteria here and here. Most factors we use in admission favor wealthy students. Some students in wealthy school districts begin writing college admission essays in their freshman year. On the other hand, some students who are less advantaged send in the first draft they type on the screen while filling out the application.

But this argument is effectively, “Let’s have more bad,” and actually reinforces the “by the way, GPA in college prep courses is the only thing that matters,” point. It’s the only thing that matters because going to four years of high school and doing that work more closely resembles four years of going to college than a three-hour test resembles four years of going to college. I don’t care if colleges want to use essays and recommendations as a way to signal interest and nothing else; or if they want to require recommendations to see how well the English teacher at the school writes. It’s their college, and it should be their choice. Just like using tests should be the choice of the college, rather than something The Agencies coerce with incomplete truths.

Point 8: Tests measure native ability. Believe it or not, this is the original premise of the SAT. The “A” stood for “Aptitude,” and the test’s founders generally believed that some races and cultures were inherently superior to others. There are lots of good articles and books on this, but try this short interview on the PBS site to summarize it. Now, SAT is just the name of the test; it’s not an acronym, and it doesn’t stand for anything, in one of the most poignant truths every uttered. And the College Board has disavowed the original founders’ visions, although the Educational Testing Service (a company that used to create test questions for the SAT) apparently still has a library named for Carl Brigham.

In fact, lots of people who still espouse racist ideas still believe in some of these powers ascribed to tests. In fact, when The College Board created a system to put SAT Scores in context, lots of people thought that (but not the test) was racist. Go figure.

Lots of people who bought into the “some cultures are superior” had a pretty clear idea about who those superior people were: White people of northern European and British Isles heritage. Coincidentally, I’m sure, they happened to be White people from northern European and British Isles heritage. Being White and of northern European ancestry myself, I really don’t have anything against people from that part of the world. I just don’t think there’s any innate superiority in our genes. (Nicholas Lehman, the author of the Big Test, reminds us to look back with context: “…one of the difficult things about history is not being anachronistic. That is, not applying the standards of the present to the past. So it must be said that in 1920 virtually every respectable person in the United States was an unacceptable racist by today’s standards. Just as an example, remember, you could not find a man who believed that women should occupy positions of authority in 1920.”)

One of the groups they despised was Jewish immigrants, especially from Eastern European countries. When those students worked hard and got good grades, it was hard to deny them when you admitted wealthy White kids from prep schools who didn’t have the same grades. So, a tool to root out natural genetic superiority seemed just the thing they needed. The SAT supported the Jewish quotas many highly selective universities had in the first half of the last century.

The tests don’t measure native ability or intelligence. The creators thought they might measure something psychometricians call “g.” It’s not a nice idea. You can skip clicking on that link.

The people at Compass Education Group know a lot about standardized tests, because they teach students how to do better on them. Adam Ingersoll, with whom I did a presentation at a few regional ACAC conferences in 2018, used a slide that suggested the tests reflect Content Knowledge, Formal Preparation, Speed and Time Management, and Emotional Control. That sounds about right to me.

Speaking of which, the people who create the tests have often said that formal test-prep doesn’t work, which would suggest they still believe there is some element of innate intelligence measured by the exams. Of course, now The Agencies both offer free, online prep classes.

So you sort of want to ask which one it is.

Point 9: If low-income students don’t take a test because they don’t need it for college admission, colleges won’t be able to find them. This has some validity under the current way we operate, in which The Agencies sell (or, technically, lease) names of test takers to colleges for recruitment purposes. But of course, it’s only a problem if you believe that’s the only way we can operate. If the federal or state governments want to make college access happen, they can find a way to create databases of students enrolled in each state, along with other data that might make them appealing to colleges. And the states could actually make money off the process.

-o-

My proposal

In addition to (probably) not talking to the media about tests any more, I want to suggest a way to make me stop talking about standardized tests all together. For the record, I’ve never been opposed to colleges using them if they want; I’m opposed to the misuse of tests (such as one highly selective university telling students, “we really like a 32, but we love a 33, or the fairly draconian SAT cuts Harvard apparently uses in its admissions evaluation system, their claims of holistic review notwithstanding.)

Here are the details:

- IPEDS stops collecting incoming freshman class test scores

- CDS publishers take test scores off the survey

- NACAC issues a statement saying colleges should not publish the scores anywhere

- College Board and ACT do the same. Going first would be an enormous sign of goodwill. (That sound you hear is probably people at The Agencies laughing at the idea of goodwill between them and me. However, I’ve said on numerous occasions that I honestly like almost all the people I’ve met who work at either place; I talk to them at conferences, and have even had a few beers with them over the years. I just don’t like their corporate business practices.)

Then, colleges can use them all they want. And, presumably, they’ll be free to admit students with lower scores without fear of hurting themselves in the rankings. And I shut up.

If you’re a journalist, and you’ve read this completely, and you have a new question about the tests, please feel free to email me, but it’s still unlikely I’ll reply. I’ve enjoyed being a go-to guy for this for several years, but someone else needs to take over.

Let me know if you want to be that person, or if you want to nominate someone to be it.

-30-

Can you remind me of the password?

Erica Peale Design

http://www.ericapeale.com

703-899-7825

LikeLike

It’s still a draft and I sent it to a few people for editorial review. I’ll take the password off when it’s ready to publish.

LikeLike

I would love to follow your Blog and I thought I had a password, but for some reason it is not working. How do I get one?

Sarah Soule (Middlebury Union High School, Vermont) – this is my personal email, my school email is ssoule@acsdvt.org

Thank you!

>

LikeLike

Hi Sarah. It’s still in draft form, and I sent it to a few people for review. I’ll take off the password when it’s ready to go.

LikeLike

Sorry I’m being dense- what is the password?

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

I’m still working on it

LikeLike

Hi Jon,

Did you want me to see this?

No need to reply if I wasn’t one of the “chosen ones.” : )

Claire

Claire Nold-Glaser, M.Ed. (she/her/hers) College Planning Help 1407 116th Ave NE, Suite 110 Bellevue WA 98004 425-373-1192

Member: NACAC, PNACAC, HECA, WSCA, LDA President-Pacific Northwest Association for College Admission Counseling

HECALogo

Please LIKE College Planning Help on Facebook !

LikeLike

Hi Claire. Are you saying you can read it? It’s still password protected, or supposed to be.

LikeLike

Hi Jon! I mist have missed something—what is the password so I can log in? 🙃 On Fri, Jan 10, 2020 at 6:09 PM Jon Boeckenstedt’s Admissions Weblog wrote:

>

LikeLike

Hi Jon,

In case your readers want to see SAT score distribution by ethnicity, here is a link to the publicly posted data set from College Board. This is less granular than the ACT data you shared, and I haven’t Tableaued it. See page 5 https://reports.collegeboard.org/pdf/2019-total-group-sat-suite-assessments-annual-report.pdf

Persevere to page 8 and you will see how high school GPA correlates to PSAT scores for sophomores and juniors. These data worry me. Even if grade inflation is overblown or a non-issue (see your Point 3, above), it’s troubling to see HS GPA correlate so strongly to PSAT /SAT scores when we know higher test scores also correlate strongly to higher family income and lower POC-ness.

You can see similar trends in individual states, even when the participation levels and total scores differ greatly between sophomores who almost all take the PSAT and juniors who self-select (like Idaho). https://research.collegeboard.org/programs/sat/data/2019-sat-suite-annual-report

When I worked at College Board, very reliable people told me that self-reported HS GPA holds up under scrutiny and audit.

I respect your desire to move on to other issues and may post this in CAC for your successor.

xo Dave

LikeLike

As a test prep person who specializes in working with intelligent kiddos with LDs, I’d love for the tests to go away; I’d love to be put out of business. You failed to mention this group of kids who are absolutely harmed by these tests. This quote always hits home to my folks when it comes to these tests: “if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” These tests (and arguably the state standardized tests as well) make these smart kids limit their options. I know because I was one of them in the 90’s…that’s why I work with this group of kiddos….I struggled to be “good” at these tests (APs included); I went through dozens of tutors who didn’t “speak” my language when prepping for the GMAT (aka they were naturally good at them but couldn’t work with someone who didn’t think like the average person), I could afford it. Anyway, Great article and I’m sharing on my Twitter.

LikeLike

Phenomenal summary, Jon. Bravo and enjoy your well-earned rest on this one.

LikeLike